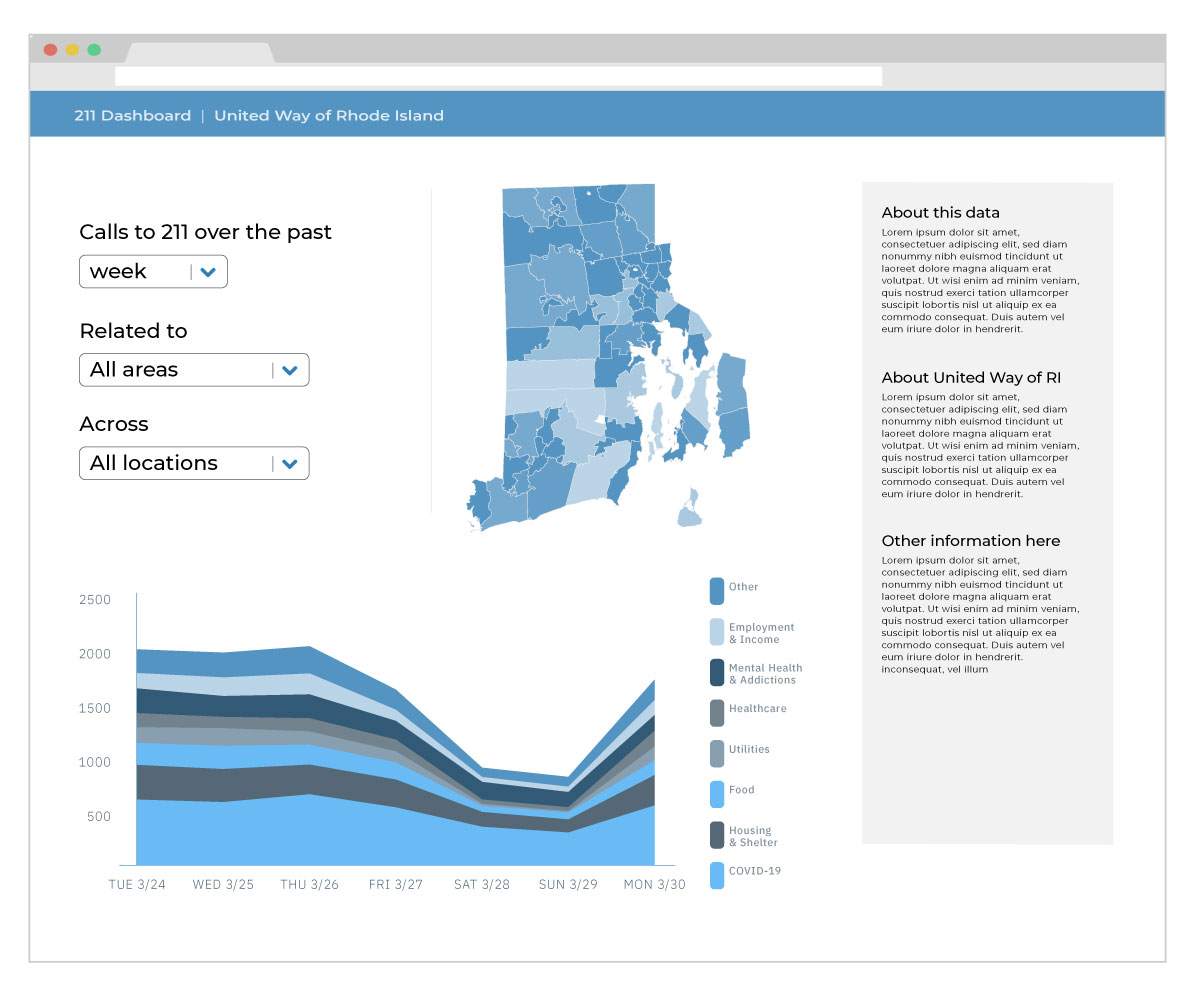

In the previous post, we covered the background and the decisions on the tech stack used for the United Way Rhode Island 211 dashboard. This post will describe how we used Vue.js to build the architecture of the dashboard based on the design of Ben Guhin Delphine in the featured image above.

- Part 1. Decisions on the Tech Stack

- Part 3. Rendering the Visualizations

- Part 4. UI/UX Refinements from Stakeholder Feedback

The Overall Architecture of the Dashboard App

For simplicity, we chose to deploy this app as a static page, using GitHub Pages as a backend because neither the volume nor the complexity of the data justifies the additional cost of a backend. This also allows the United Way a wide range of future hosting options to deploy the app.

Centralized state management in with Vuex

With Ben's design it is easy to see that there are two types of the components in this app: the drop-downs on the top left that serve as filters for the 211 call data and the two charts that visualize the data based on the filter selections. Therefore, in the Vue app, there are two types of states that need to be persisted with Vuex store: the 211 data itself and filter states. For the former, we load the 211 call data from a CSV file when the app loads. For the latter, we use an object to store the state of the filters, which can be bound to the values of each of the drop-downs.

Once the 211 data is loaded and stored in the Vuex store, the two chart components can receive them and the filter states. Within each chart component, we can then apply the filters to the 211 data and update the charts. In other words, each component will also maintain a state of its own filtered version of the 211 data. d3.js is well equipped for both the heavy-lifting in processing the data and the rendering of the data visualizations.

Handling state change in Vuex

To make the dashboard more interactive, we also need to enable interactions between the two chart components. For example, when the users click on one region in the map on the chart, the stacked area chart should also update to focus on the 211 calls in that geographic region. This type of interaction can be done through mutating the state in the Vuex store: during the rendering of the map, we can use d3 to listen to the click event on each SVG path of the map. Once a click happens, an event is then emitted, which can be handled by the event handler in the root component of the Vue app. The handler then dispatches an action to Vuex, which commits the mutations and updates the filter persisted in the store. The changes in filter states will trigger a reactive update to the other visualization, which will be re-rendered. This way, we compartmentalize Vue and d3 to make the two visualizations talk to each other through centralized state management.

Building the Skeleton of the App

We initialized the dashboard app with vue-cli, which comes with a wide range of options in creating a standard Vue app and the type of features (e.g. Vue-Router and Vuex) it will include. It also has a GUI for the same purpose. The Vue CLI website has detailed instructions on how to create a Vue project.

Loading data files with concurrency

Most of the components in this dashboard depend on the 211 data: the filter controls need to display all the regions and call categories that exist in the data, not to mention the charts. Therefore, we first need to load the 211 data into the app. This is a fairly large .csv file (approx. 2.5MB) for a web app saved in a "tidy(long)" format. (We'll return to this size issue in Part 4.) The file looks like the following, with each line showing a city in Rhode Island, and the number of calls in a specific category on a given date.

city,type,date,count

Barrington,All Categories,2020-03-01,0

Barrington,COVID-19 Control,2020-03-01,0

Barrington,Disaster Services,2020-03-01,0

Barrington,Food/Meals,2020-03-01,0

Barrington,Health Care,2020-03-01,0

There are also a few other data files that need to be loaded: a geojson file that provides the city outlines which the map is based on, and a json file that shows the population of each Rhode Island city, which will be used to calculate per 1000 capita number of calls. We can use JavaScript Promises to concurrently load these files to reduce the time of rendering block. The code looks like this:

// We have to make the created() lifecycle method async since we

// are using await ES6 syntax in the body.

async created() {

let [data, topo, pops] = await Promise.all([

d3.csv(`/dashboard_data.csv`, row => { // loads the 211 call data

row.date = new Date(row.date) // convert date column to Date

return row;

}),

d3.json(`/ri.topo.json`), // loads the topojson for the map

d3.json(`/ri_pops.json`) // loads the RI city population file

])

// More operations based on the data from here ...

}

A few observations on the above code:

- Data loading happens in the

created()lifecycle method of the root component, which means the data will be loaded when the root component is being created. We can make this methodasyncbecause we are usingawaitin the function body with the ES8async/awaitsyntax. - In d3 v5, data loading methods such as

d3.csvandd3.jsonreturnPromises.Promise.all()takes an array ofPromises and returns aPromisethat resolves when all of the promises in the array are resolved. This ensures that each of the function calls in the array is executed concurrently. - We can

awaiton any function that returns aPromise, becauseasync/awaitis basically syntactic sugar that makes it easier to work with functions that returnPromises. - We also used the array deconstruction syntax to assign the result of

Promise.all()function to individual variable to be referred to later.

Filter controls with Vue-Formulate

Vue-Formulate is a light-weight library for creating forms in Vue apps. It essentially provides a Vue component wrapper for every HTML form element and provides data binding and easy form validation. We used a <Vue-Formulate> component for each of the drop-downs. For example, for the first drop-down:

<FormulateInput

type="select"

label="Calls to 211 Over the Past"

v-model="options.range"

:options="{Week: 'Week', Month: 'Month', 'Select Dates': 'Select Dates'}"

@input="handleRangeChange"

/>

Note that we wrote an event handler for when the value changes in the drop-down. With vanilla html select element, this event is v-on:change, but for Vue-Formulate, this event is v-on:input. The use of @ is simply a shorthand to replace v- prefix in Vue.

Next up

In this post we covered the overall architecture of the dashboard app and a few details in creating an outline of the app. In the next post, we will describe how we made the data visualizations. Part 3. Making the Visualizations with d3.js.

How to cite this Reflection: Xu P. (2021, February 21). The Making of a Dashboard - Part 2: Building the Skeleton of the App. The Policy Lab. https://thepolicylab.brown.edu/reflections/making-of-a-dashboard-part-2